With their red-tinged skin and elaborate braids, Himba women are among the most recognizable in Namibia. Their distinctive appearance has piqued the curiosity of many travelers, and our tour of Northern Namibia included a visit to a Himba village so that we could learn about their culture.

Traditionally, the Himba are a semi-nomadic people living a pastoral lifestyle in Northern Namibia and Angola. In modern times, groups of Himba have become less nomadic and settled in small villages in the Kunene and Kaokoland regions of Namibia.

We visited a recently settled village that is unique because it is located a plot of land owned by a white man who married a Himba woman. (We did not meet him as he was out of the village on business, but we met his wife. What stuck out to me most about her was that she was constructing beaded bracelets to sell to the village’s visitors, just like the other women in the village.) Our guide to the village was a Himba woman named Maria who wore Western clothing and kept her hair cut short. Maria explained that she could no longer wear traditional dress because she had left to pursue her education, and she later pointed out a young woman in the village who had done the same.

Just after meeting Maria, we were mobbed by children. There are more than thirty orphans in the village, and their care is a responsibility shared amongst the village, which is mostly inhabited by women and children, with many of the men working in various Namibian towns. As we walked into the village, the children scrambled for the chance to hold our hands or climb into our arms.

Himba women are highly recognizable for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the mixture of butter and ochre in which they cover every bit of themselves, from their faces to their bare chests to their limbs. The mixture, which gives their skin a reddish color, is both cosmetic and practical, as it moisturizes their skin and protects them from the sun in addition to beautifying them.

Another defining characteristic of Himba women is the way in which they wear their hair. Their hair is adorned with leather and plaited with extensions made from cows’ tails and then covered nearly completely with the same mixture of butter and ochre just on their bodies.

While we were watching a woman style another’s hair, a process that looked painful and gave me unwelcome flashbacks to having my own thick hair pulled through the tiny holes of a highlighting cap, there was a great commotion in another section of the village. A snake had been spotted in a tree! Suddenly, the entire village was alive: men were chasing the snake, pelting it with rocks; children were running alongside, tossing stones and shrieking; and women were swatting at the children, trying to discourage them from getting near the snake. The snake, once killed, was revealed to be of the non-poisonous variety. Nonetheless, Maria explained, snakes are a very real threat to the Himbas and must be taken seriously.

We learned about many other aspects of the Himba women, from the symbolism in the types of jewelry that they wear (there are certain necklaces that always worn and only removed once they have children, certain necklaces that are only worn once they are married, and many other styles of bracelets and anklets that signify different things) to the fact that women never bathe with water and instead take smoke baths. One woman demonstrated to us how to take a smoke bath: it involved lighting fragrant wood and herbs and then leaning over it, much in the same way that you might steam your face.

While it was interesting to learn about the Himba culture, which is so different from our own, the experience also left me unsettled. As Maria guided us around the village, stopping in front of Himba women, each with something to show us, it felt as though we were being led around a zoo to gawk at the oddities. The fact that she repeatedly implored us to, if interested, take pictures also felt off-putting.1 I struggled to discern whether the women were sitting outdoors performing these tasks for our benefit, or whether this was a normal part of their daily lives. In either case, it felt like they were turning themselves and their culture into commodities for tourist consumption, and it made me feel uncomfortable.

On the other hand, Maria stressed how tourism benefits the village. The money they earn from the meager entrance fees and from the sale of their handicrafts helps them care for the orphans and obtain things like modern medicine. In the end, we thanked the women for teaching us about their culture and purchased some bracelets.

Where We Stayed:

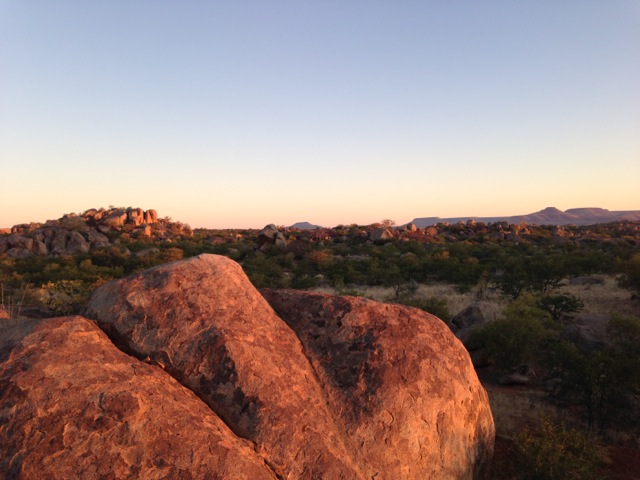

☆ Hoada Campsite. Four-and-a-half goats. The campsite had no power, but it had such amazing scenery, set amongst giant granite boulders. We scrambled atop rocks to watch that evening’s sunset and the next morning’s sunrise. There was a small bar tucked into one of the surrounding hills, which felt as if it could have belonged on some sort of Buzzfeed list of “Bars to Visit Before You Die,” although it was poorly stocked and perpetually short on change.

1 This post is currently illustrated with images culled from the Flickr Creative Commons. We may, however, replace these pictures with shots that were taken by other members of our group.