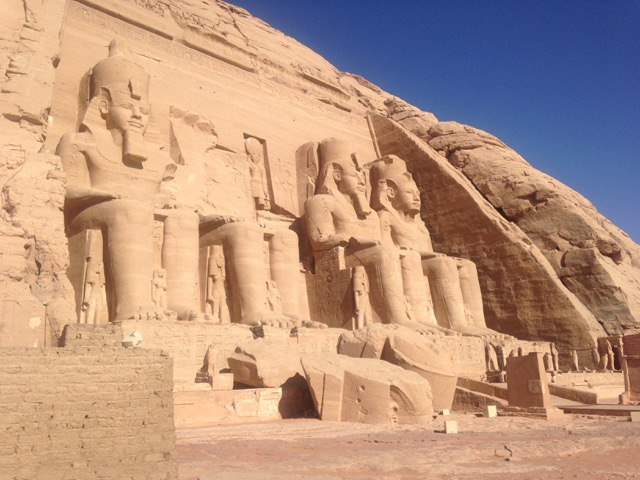

I have always, always wanted to see the Sun Temple at Abu Simbel. Ever since I stumbled across a National Geographic article about it as a child, I have been equal parts fascinated by its imposing facade and its methodical relocation, saving it from certain doom. I found that our guidebook summed it up aptly with the following: “[Y]our mind boggles at its audacious conception, the logistics of constructing and moving it, and the unabashed megalomania of its founder.” (emphasis mine because, really, what a great phrase).

Abu Simbel is in Southern Egypt, very close to the border with Sudan. It is located in what was once Nubia, before Nubia was divided between Egypt and Sudan, which is why you may see Abu Simbel referred to, in this blog post and other places, as one of the “Nubian monuments.”

Although it is possible to stay in the village of Abu Simbel, most people (us included) visit as a daytrip from Aswan. Groups from Aswan travel the nearly 300 kilometer route in a convoy of vehicles leaving at 4:00 a.m., reaching Abu Simbel around 8:00 a.m. and giving you two hours at the site before making the return journey back to Aswan.

A word on arranging transportation from Aswan: We visited two tour operators recommended by our guidebook (a relatively recent 2013 edition, it should be noted) and found them both distinctly unimpressive. The first, located in a spartan office beneath a hotel currently closed for renovation, didn’t want our business at all. When we inquired about transportation to Abu Simbel, the man behind the desk interrupted our query and told us we were better off taking the public bus (an idea which we would not have been opposed to, had we been able to obtain any concrete information on this bus from anyone). We thought it was strange at the time, and we thought it was stranger still when we spotted one of this company’s vehicles transporting people in the convoy the next morning.

The second, a man based out of a dodgy-looking hotel, seemed creepy and represented everything we disliked about negotiating tourism in Africa. While blowing cigarette smoke in our faces, he showed us some pictures of the temples in a binder, told us that there were “just two” seats left for the next day’s trip to Abu Simbel, and then asked us if we knew how much the price was before he quoted us anything. In the end, we just arranged transportation through our hotel in Aswan, the Philae.1 We appreciated the fact that they offered us a reasonable quote without the need for any haggling theatrics, and saved us from dealing with those other characters.

We were instructed to be ready to go by 3:15 a.m., and so we waited, barely awake, with our hotel-prepared breakfast boxes on our laps, until a small minivan picked us up at 3:30 a.m. There were two other couples in the minivan and we picked up another two people before we joined the line of vehicles that would become the convoy. Despite the noticeable dearth of tourists in Aswan, there was a long string of full-size tourist buses and packed minibuses lined up to make the journey to Abu Simbel. Where did all these people come from? we wondered. Had they been hiding on the docked cruise ships moored along the Nile in Aswan?

Frankly, the sheer quantity of tourists made us a little nervous. Having been spoiled by our low-season travels through the rest of Egypt, we worried that having to share the space with this many people – especially after our solitary experiences at Edfu and Kom Ombo – would ruin our time.

Luckily, we were wrong. Everyone was respectful of each other’s space and time – and likely a little groggy from the early morning transit. Plus, the large tour groups (which comprised a majority of the visitors in the convoy) tended to stick together, so it was not difficult to dodge them.

Besides, there was plenty of room for everyone. The Sun Temple is often thought of as synonymous with Abu Simbel, but the site is also home to the Hathor Temple of Queen Nefertari.

Everyone flocked first to the Sun Temple, so we headed over to the Hathor Temple. Surprisingly, we were the only people to adopt this strategy, and we had the place completely to ourselves. It was unreal. The interior paintings are so clean and bright, they look as though they could have been done ten years ago rather than thousands.

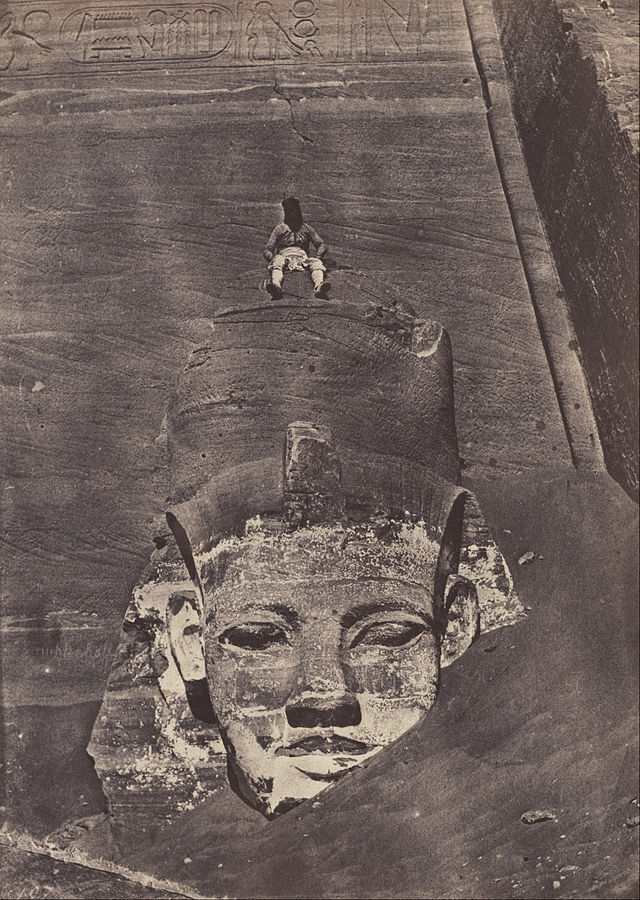

One of the reasons that these temples have been so well-preserved is likely because they were almost completely buried in sand.

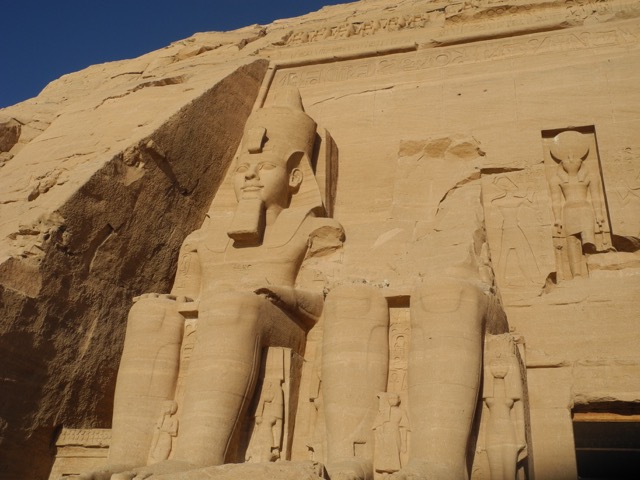

Like the Sun Temple, the Hathor Temple is fronted by several colossal statues. Standing over nine meters tall, they depict Rameses II and his queen Nefertari. Smaller figures of their children stand around their knees.

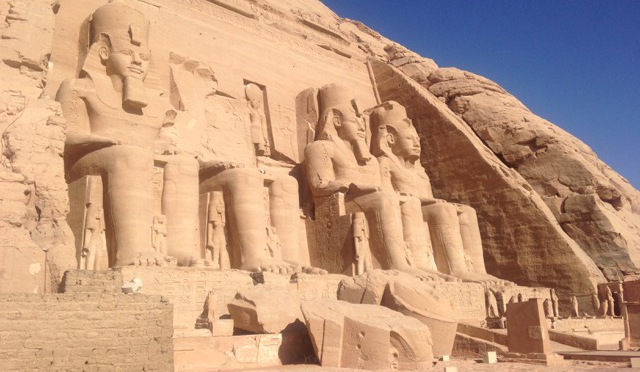

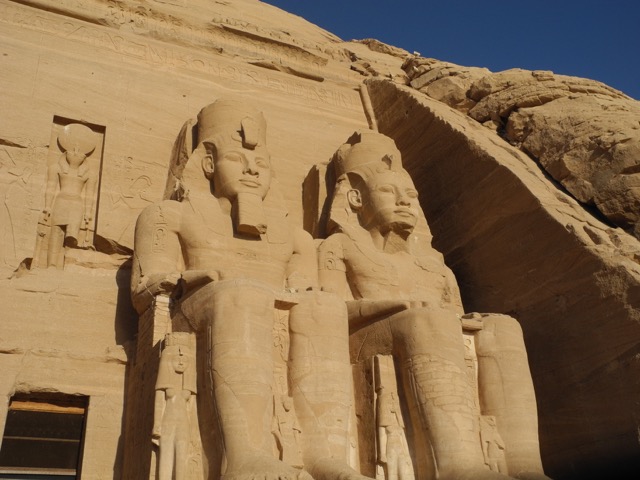

By the time that we made our way over to the Sun Temple, the main attraction, the crowds had cleared a bit and we were able to get some nice shots of the exterior without a bunch of strangers in them.

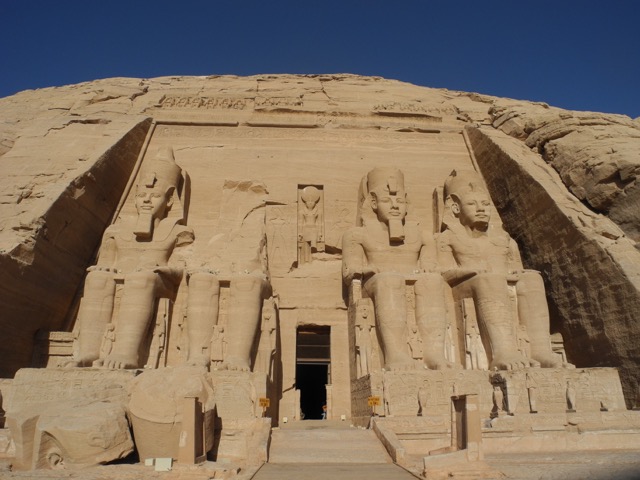

If I had worried at all that the Sun Temple would be less impressive in real life than it was in images, I needn’t have. The sheer scale of the facade is breath-taking: the four colossi of Rameses II are 20 meters tall.

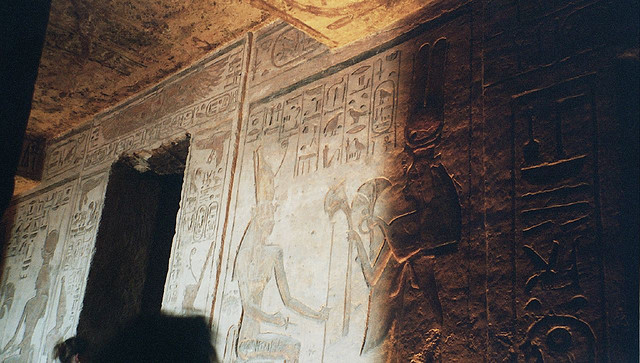

In some of these Egyptian temples, the exterior has been the best part, but that wasn’t the case here. The interior was detailed, well-preserved, and, because you see it less often, arguably more interesting than the exterior.

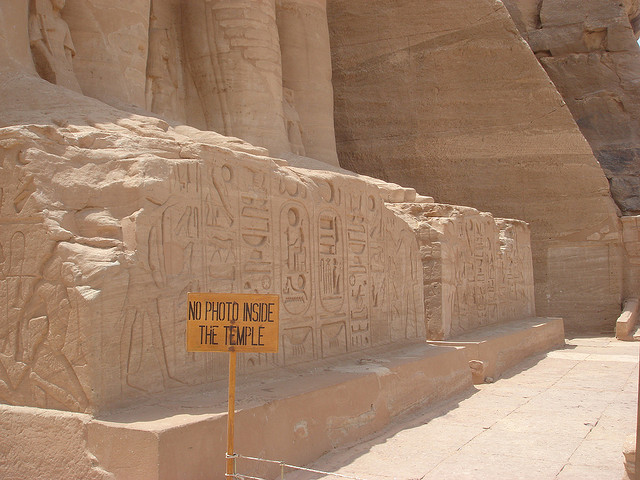

But first, this is why all the pictures in this post of the interiors of the Sun Temple and Hathor Temple are from Flickr:

You enter the temple directly into a hypostyle hall lined with eight enormous columns representing Rameses II as Osiris, the god of the dead. The columns are in various stages of disrepair, but they are largely intact and ancient paint still clings to them.

I also like the following image, which, while not as clear a shot of the columns, better shows the mood inside the temple: dark and cavernous, with blindingly bright sunlight streaming in over the heads of tourists.

The temple has more rooms than I anticipated, including a number of rooms leading off the main room. These rooms are thought to have been used to store cult objects and tribute, and are covered in carvings.2

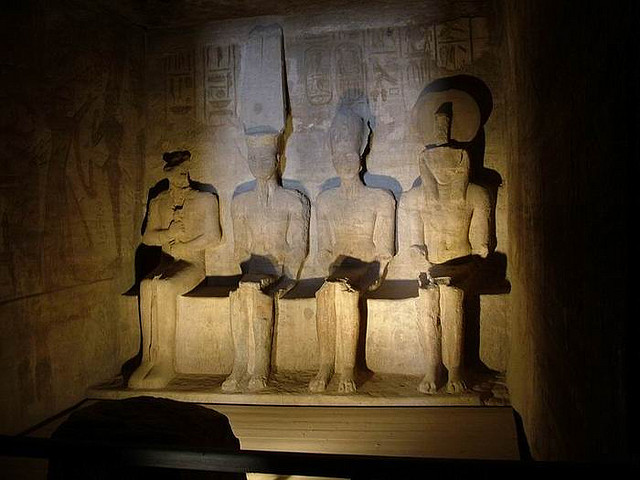

In the back of the temple is the sanctuary, containing four cult statues. Once covered in gold, these represent Ptah, Amun-Re (a form of the sun god), Re-Herakhte (another form of the sun god), and a deified Rameses II.

The temple was constructed so that the statues would be touched by the sun at dawn on February 21 (Rameses II’s birthday) and October 21 (Rameses II’s coronation). Now, after the relocation of the temple (see infra), the dates of the solar event are February 22 and October 22.

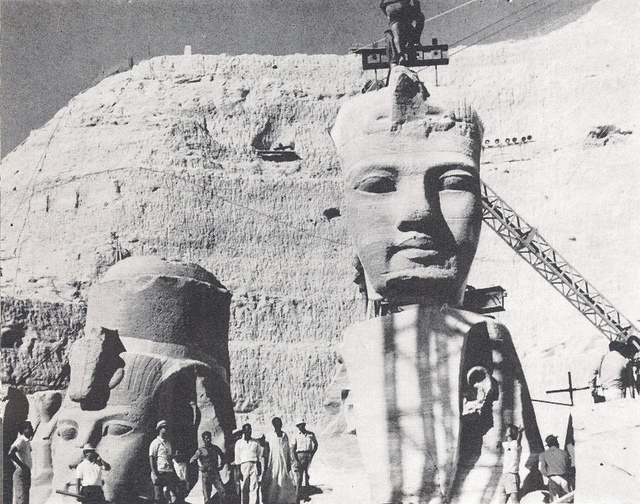

The temples are incredible, but what’s really mind-blowing is that they are here at all. In the early 1960s, construction began on the Aswan High Dam. The dam across the Nile was important for flood control, irrigation, and generating hydroelectricity, but the rising waters of the resulting Lake Nasser (which, to this day, is still one of the world’s largest manmade bodies of water) threatened to submerge a number of the Nubian monuments (Abu Simbel among them). UNESCO initiated an international fund-raising effort, and twelve of the threatened monuments were heroically dissembled, moved, and reassembled – four of them being given as gifts to donor nations, including the Temple of Dendur, which can be visited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

That’s right: the temples at Abu Simbel were carved up and moved, block by block, to a new location 200 meters back from the waters of Lake Nasser and 65 meters higher.

We had been worried that the convoy would not allow us adequate time to see the temples, but we had plenty of time to enjoy them at a leisurely pace … and even snap a few sweaty selfies.

In conclusion: Abu Simbel lives up to its hype. Go see it.

1 In case you need a reminder how much I loved the Philae, here’s the link to our previous post in which I gushed over it.

2 To see one of these long rooms, click through to this incredible non-Creative Commons Flickr image.